The other day I got tagged on a Twitter thread started by Wicked Witch of the Test about people with a background in linguistics who’ve ended up in testing. That prompted me to think about the language concepts I've found valuable in my day job, then I started listing them, and then realised how many of them I've mentioned here over the years.

This post is one of an occasional series collecting some of those thoughts.

If you're not familiar with the term syntax, you've probably heard of it by another name, grammar. It's the set of rules that defines the acceptable combinations of words in a language. Most native speakers have an instinctive grasp of it in their language, even if they were never taught it explicitly.

Knowledge of English syntax is what can tell you that the first two of these are legitimate structures (even if the second makes no sense) and the third is not:

- As a customer I want to log in using two-factor authentication to protect my account.

- As a hexagon I want to weep over Germans to offset the time.

- Protect customer to log in account as using authentication to want two-factor I my a.

Unlike the syntax of a programming language, which tends to be strict and unambiguous, natural languages have fuzzy grammars. For example, linguists can generally agree on a core English grammar while also disagreeing about specific details.

This holds true for different varieties of a language such as regional dialects, and even for indvidual speakers within a language group. On top of that, native speakers have typically internalised multiple grammars for their language and will switch between them depending on the context.

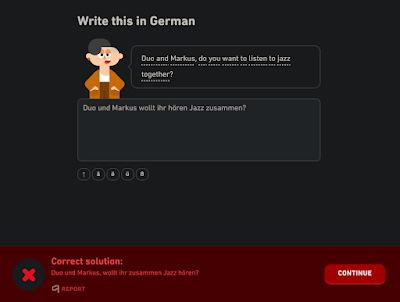

As a native English speaker in a company based in Germany I feel privileged to be able to collaborate with colleagues in my mother tongue. In those conversations I often hear the grammar of other native tongues peeking through into English ... although nowhere near as frequently or intrusively as my English grammar stomps all over my feeble attempts to learn German, as the image at the top shows.

Even if natural language grammars were strict, there's another way they're unlike programming languages: a phrase in a natural language will frequently be ambiguous even if it is grammatically correct.

The fuzziness of our grammars is balanced to some extent by the natural inclination of listeners to make sense of what they hear ... even if that means inventing stuff that wasn't said.

This can be very helpful. When I screw up the word order in my German exercises a native speaker, particularly one familiar with English speakers mangling their language, would have no trouble understanding what I meant.

Unfortunately, and you won't be surprised to hear, it can also be unhelpful. Did you find yourself wondering what As a hexagon I want to weep over Germans to offset the time might mean? Did you perhaps even begin to try to engineer a context in which it was something that you could work with? You are not alone, as Chomsky's "colorless green ideas" sentence famously shows.

Working in cross disciplinary teams with multiple native language speakers we will naturally acommodate each other's syntactic pecularities. Choosing when to question immediately, when to wait to question, and when to assume you've understood correctly is an interesting problem. But syntax is not the only cause of that problem, just another angle to be aware of when choosing your tactics.

The term grammar generalises to describe structures such as Given-When-Then which can be used to describe scenarios in software development. If a sentence is in Given, then it's a precondition but if the same sentence is in Then it's a postcondition. The structure helps to disambiguate the meaning.

Take these two examples which use the same English clauses to suggest very different causal relationships, and perhaps an unusual lollipop in the second case:

Given there is a lollipop and a child

When the child licks the lollipop

Then the lollipop shrinks

Given there is a lollipop and a child

When the lollipop shrinks

Then the child licks the lollipop

The strength of syntax to govern structure but not meaning is emphasised in these similar constructions:

Given the child licks the lollipop

When there is a lollipop and a child

Then the lollipop shrinks

Given the lollipop shrinks

When the child licks the lollipop

Then there is a lollipop and a child

They fit the prescribed grammar but their meaning and utility as acceptance criteria is much more vague. In fact, as I read these back in the draft of this post, I felt that they had a whiff of syllogism about them, another three-place grammatical structure:

All mortals die

All men are mortals

All men die

But I fear that I was doing exactly what I cautioned against earlier, and finding an interpretation in an attempt to make some sense of the words.

Grammars generalise away from spoken and written language too. Designers might talk about a visual grammar and perhaps produce a style guide for a user interface in a product to help provide a consistent experience where the same kinds of controls have the same kinds of functions in the same kinds of contexts.

Descriptivism and prescriptivism

are interesting concepts in linguistics. A descriptive grammar attempts

to document actual usage by the speakers of a language while a

prescriptive grammar lays down which uses are preferred or even correct

and acceptable. Both approaches have value and some kind of compromise is usually required.

The descriptive approach lets everyone use the language they are comfortable with and so is inclusive but risks shallow understanding or, worse, complete misunderstanding.

Recognising the grammars in play in any context can be extremely valuable. With that knowledge we can more easily and precisely- understand and make ourselves understood

- observe non-surface differences and patterns

- deliberately contradict the grammar when it makes sense to